The mess!

January 2023

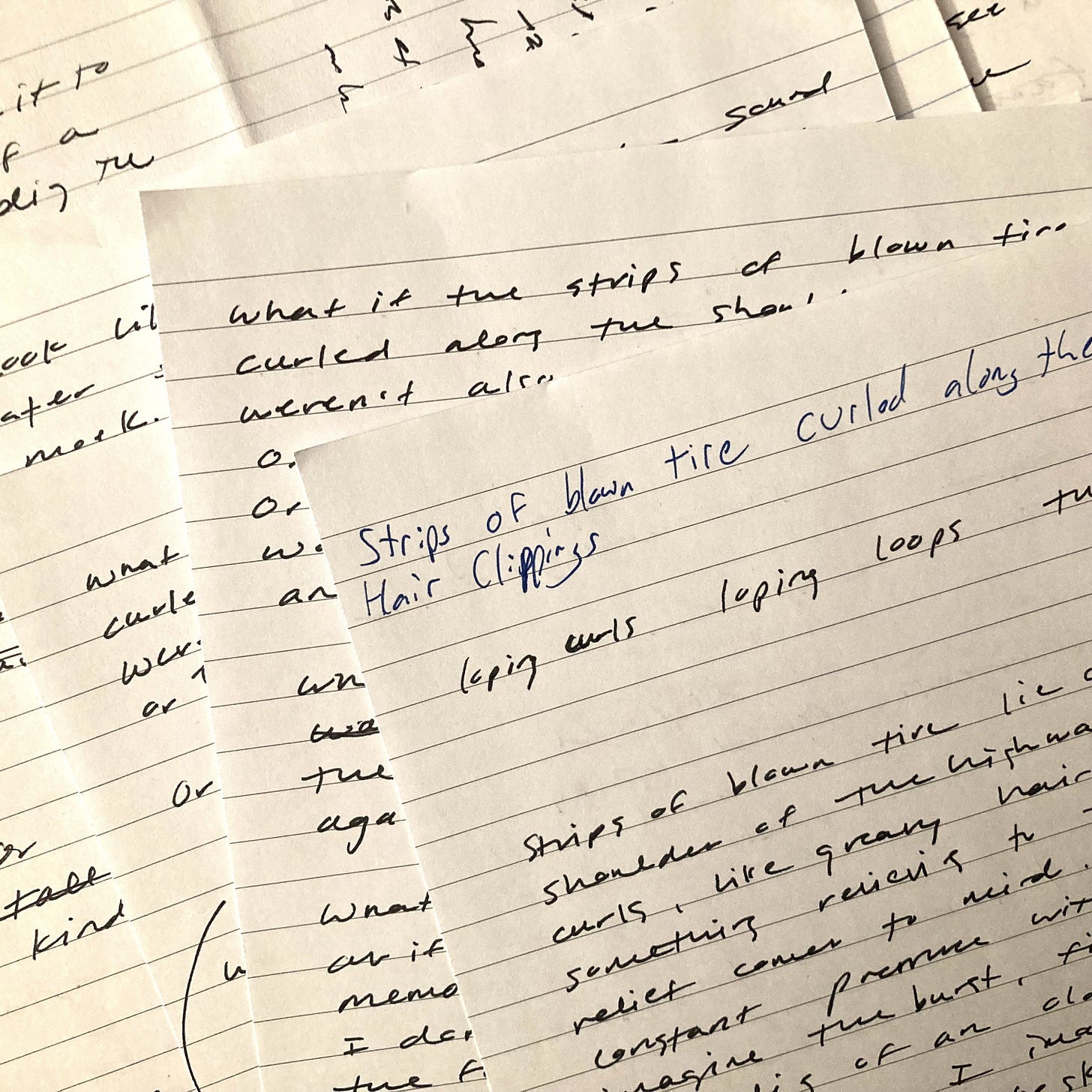

Strips of blown tire curled along the shoulder. Hair clippings. We’re driving southeast on I-29 when I ask Matt, in the passenger seat, to open my notebook and write this down. It is a deliriously hot July morning, so hot the day seems sapped of its color, the white sky and the dry fields barely distinguishable, the view out the windshield blinding. The cabin is full not of sunlight but of glare, accusatory reflections darting in from every mirror and fender and panel of every car that passes. If you’ve ever driven the interstate in the Midwest you know the particular spareness of it, and you know such spareness can evoke many feelings depending on the mood one brings to it: forgottenness; desolation; a deep, cutting loneliness; a delicate, artful loneliness; peace; relief. The farm houses tucked among pockets of trees, grain silos both working and rusted, the stoic memorials, sometimes a single cross, sometimes a beautiful, windblown knot of flowers and ribbons and photographs. Billboards for antique malls and firework tents and boot dealers and Cracker Barrels and “Life is Precious,” a seemingly innocent statement that becomes less so as one gets older and begins to understand. In health class, starting at age nine or ten, they teach you about menstruation, what it is, why it happens, what it will feel like, how to deal with it, but they don’t tell you that, upon entering puberty, you become inducted into a group of people whose bodily functions will now be fought over by strangers in public. They don’t tell you that you’ll see your innards debated on news programs and editorialized in the paper and screamed about online. They (your innards) might even get their own section on the ballot handed to you in an elementary school gym by a smiling volunteer. They don’t tell you that every time you leave town (and sometimes when you stay in town) you’ll be subjected to billboards confidently informing you of the point at which you split, and become two people. You learn all that by yourself. Another inescapable classic—“Jesus is love” or “I love Jesus” or “You love Jesus, you better love Jesus.” Et cetera. I remember these messages first prompted curiosity—I didn’t grow up in a remotely religious household, and I was unfamiliar as a young child with even the basic premise of religion, not to mention the foundational stories of Christianity—who is this Jesus person, I wondered. I learned soon enough, and curiosity morphed into a deep unease as friends and strangers alike informed me that I would burn forever in a fiery pit unless I let them help me change my mind. Now, as an adult, and having lived for a period of time outside the Midwest, these billboards still make me feel uneasy, but there is also a slight, strange comfort. Or familiarity confused for comfort. This is a person I know how to be, this is one of the first people I ever was—the secular person amidst a specific breed of Christian who treat non-Christian individuals not as people but as souls to be collected like coins in Super Mario. So—we’re about three Jesuses, four fetuses, and two Cracker Barrels into our drive when strips of blown tire begin appearing on the shoulder of the road. Some are so thick they sit upright, curled up and back over themselves like dancers stretching. Others lie flat, and some wouldn’t be recognizable on their own as pieces of tire at all, just frayed black fibers soon to be woven into birds’ nests. They come at a clip, these pieces, creeping closer and closer in the windshield before their speed suddenly picks up and they zip past. Their number is shocking and puzzling. For nearly an hour we don’t go without seeing one. Wouldn’t so many destroyed tires speak to a pile-up so massive it would’ve closed the interstate, or at least made the news for its sheer devastation? Even if it’s an accumulation—separate instances of blown tires over the course of one or two months—the place is so flat and the wind so fierce it seems the debris would have been blown away. I’m watching the zooming tire pieces and puzzling over these things when a vivid image of hair clippings blooms in my mind, and that’s when I ask Matt to get my notebook. Strips of blown tire curled along the shoulder. Hair clippings. He writes it down and I forget about it. We arrive hours later at the Airbnb my extended family has rented, a four-bedroom house in the Ozarks. My mom immediately declares war on the flies that have laid claim to the place; flyswatters materialize, makeshift fly tape is hung on the back porch, and we all slip inside and outside quickly, less to prevent the admission of flies than my mother’s fierce scoldings if the door is left open a second longer than necessary. I’ve been looking forward to this trip. It became an annual tradition a few years ago, and has given us all, who rarely saw each other previously, a chance to get to know one another. A few days in, though, I am desperate to get away. To my family’s credit, they’ve just been…being people. But whether I’m miserable or having a genuinely enjoyable time, my body tenses up in groups of people where I’m expected to “be myself,” and after three days, everything aches. My breathing feels stiff, and I can’t take a shit to save my life. Their most egregious affront has been being people in the morning. I haven’t regularly interacted with human beings in the morning in many years, the exception being a nine-month stint of Sunday brunches. Even then, every interaction was staged. I could readily slip into a mode whereby speaking in a specific pitch and cadence I could feign a relaxed, mildly cheery demeanor that garnered as little attention as possible while still driving decent tips. Any service industry worker is familiar. But this trip predated those Sundays. At the time, I was working a desk job from home, and I did not see faces, I did not hear voices, but spent my days with text on a computer screen. And so I did not then have any practiced front to comfortably erect, no mode to switch into, no mask to slip behind, and was thus vulnerable to the undulled horror of chitchat over morning coffee. I needed a break. I drive out to Table Rock State Park and turn into the first park entrance I find. I follow the winding road through the trees towards the lakeshore, slowing at forks to peer down the divergent roads, trying to predict where they lead. I end up in a small, deserted parking area next to a shallow inlet; the ground is rocky, and there are some picnic tables on a small peninsula that forms one of the banks of the inlet. The trees are thick. Sunlight is winking through them pleasantly, lighting up the canopy and dappling the rock. I find a flat spot close to the clear, shallow water, where waves from long-gone boats are lapping against the shore like light from a dead star or the last voice in a round, sounding out alone at the end. Strips of blown tire curled along the shoulder. Hair clippings. Although the handwriting is familiar, it’s strange to see someone else’s scrawl in my notebook. It’s like that time I ran into an old classmate I hadn’t seen in years, not in the city in which we both lived, but 515 miles away, outside a restaurant in Estes Park, Colorado. I start the way I do with most poems: by making a mess. Like a true, big, messy mess. I take an image that has moved me and dig into it, expand it, let it sprawl out on the page, identify what stays—the bright spots, moments of focus or potential focus—and what goes, and whittle it down again. There are no rules when it comes to the mess, but there is one crucial guiding point: you must follow, as faithfully as possible, that mysterious force that first compelled you write anything down at all. This is not easy, and the term “follow” by no means implies passivity. This force you’re following is an evasive specter that makes you earn the path. Trailing it entails wrestling with and through things, and trying to decipher where it might be taking you. You must decide which places to linger and which to pass through. What is worth close examination versus a glance. You might encounter pieces meant for another poem, or another writer, or another time, or no place at all. You will trace the border between language and sublime wordlessness. The specter finds joy in trying to throw you off. It likes to duck into brush and dissolve into shadows, and toss empty details and confusing imagery into your path. To follow it well you must be thoroughly acquainted with both your intuition and critical mind, and know when and where to use each. In the end, it’s just another function of the body, albeit a supremely mysterious one. In this case the image that has moved me is that of the shredded tires. Into the mess I go. There are the hair clippings, dark, damp, two-inch curls scattered in a halo on the linoleum beneath the barber’s chair, then the full, moping arc of week-old tulips over the lip of a vase, one bunch in particular, yellow, in evening light at Matt’s old house on Ashford Street (I bought tulips that year whenever I was feeling anxious or serenely happy), then the images begin to fragment and blur and clamor into my vision and make it spin—muscled streams, currents forced up, displaced, curled by the forward motion of a boat, abandoned brushstrokes if brushstrokes could be peeled up from a painting like paper can be wadded and tossed away, waves trapped in a pool, interrupting one another, impossible plaster molds of the looping gusts and eddies of wind, water, pieces of images and half images and mumblings and formless twists and pangs come swirling in, volatile, shrapnel whizzing, cutting. One function of an image in writing is to clarify a different image. This is the idea behind similes. One I often think about appears in The Secret History by Donna Tartt. The narrator is describing a massive manhunt for a missing person; it has just snowed:

It is difficult to believe that such an uproar took place over an act for which I was partially responsible, even more difficult to believe I could have walked through it—the cameras, the uniforms, the black crowds sprinkled over Mount Cataract like ants in a sugar bowl—without incurring a blink of suspicion.1

“Like ants in a sugar bowl.” Clear, precise, evocative. It is successful because it does not distract from the image of the crowd on the mountain, but clarifies it, and makes it more powerful in the reader’s eye. It wholly serves the writing. Now, alone on the rocky shore, I am watching the opposite unfold on the page in front of me. These images do not clarify but muddle, obscuring and obscured, piling on top of one another like frames of an infinitely exposed photograph and taking me further and further away from the one image—the tires—I want desperately to see clearly. They crowd there, flat and blaring on the page, emitting a hollow, off-pitch whine. At some point I have to be done for the day. I have to go back to the house and eat dinner and be social and watch my mom, now armed with Raid, gain new ground in her battle. But I return to slog through the mess each day. I hash and rehash every image and sense that comes to mind, splay them out, run my fingers over every surface and edge, pages and pages of digging and twisting. It glazes the week in a vivid, frantic sheen, all of it—kayaks tracing the shore, melty trudge to the swimming beach, heady whiff of sunscreen, midday glare. Yellow tulips flicker in the cottonwoods; the kitchen swells with tarmac: the shadow world is winking. I can’t leave it alone but I can barely face it. There are no bright spots, it’s all muck, and the reality of the tire strips keeps shrinking into the distance. I have half a mind to pull over on the way back and actually touch them to remind myself of their singularity, the quiet, spare reality of them. I dream of touching them. I really should have done that. Carving out a poem is rarely easy or straightforward, but this is different. There is a clear sense of doom, the writing giving no signs of life. What the hell is going on? I didn’t know then and I don’t know now. I return to those crazed notes every few months, hoping to find among the settled dust something I missed, or dismissed, before. I stand where I last saw the specter looking for any sign of its path. Maybe it’s not a poem I’m meant to find. Maybe someone else will find it, or maybe it will remain in the ether, in its purest form, among all the poems too good for words. Or perhaps I’m being impatient, giving up too soon. Because in the later days of writing this very essay, I do stumble upon the inkling of a possible insight: I have the wrong subject. I thought, I was so sure, that the subject was the image of the blown tires. But maybe the subject is what is shared by all the images that subsequently crowded my vision—that peculiar characteristic of the arcs of the tires, hair clippings, tulips, brushstrokes, winds, currents. The specific energy of their bending. Not mere visual similarity but a shared hum, like that of a hive. Something about this hum speaks to the mysterious bond of a found family, of kinship formed outside of blood, with one’s true people of the world. Measured by a tug in the chest, by the body’s sensing of some cord, some connection. You know what I mean—you’ve sensed that particular knowing between two people, that sharing of a deep, breathing bond running beneath the mundanities exchanged on the surface. That is what I sense among the arcs. Maybe this is my true subject, and I just fell for the specter’s dodgings. Certainly I made the mistake of being sure of anything. You should never fall for certainty that early on, amidst the mess. As soon as you do you’re hamstrung, and all other possibilities become unimaginable. With this, maybe I’ll go now, and try again.

—AKB

Donna Tartt, The Secret History, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 3.