Oranges

February 2023

1.

I eat my annual orange—the one tucked into the toe of my Christmas stocking—on the last day of the year, sitting on the back patio. After a week of sub-zero temperatures, thirty-four degrees feels positively velvet. The once unbroken expanse of snow shrinks and cleaves on the lawn, and the metal chair in which I sit holds on to the last echoes of the cold, giving the curious impression that it’s lagging in time. My hands sticky and chalky at once, juice dribbling towards my wrists. The tattered peel piled on the napkin in my lap. Soon I will enter the clamor of the world, but for now things are quiet, a hush and joy at the brink of newness. Better than any fresh start is this, just before, the final moments of what will soon be moved beyond.

2.

When I think of oranges I think of Boston. One of the joys of any walking city is the strange, lovely things you find on the ground, and oranges and orange peels were a constant: on the pavement at the Fenway stop (later Griggs Street, then Chiswick Road, Packard’s Corner), under a bench in the Commons, on the curb by the Honan-Allston library, scattered the length of the bridge to Cambridge on a shimmering Sunday. At the top of Eliot Tower, even, in a dim corner on the dusty pavement floor, a hasty pile of rind. They became for me a source of steadiness, like Orion’s Belt had once been—for a year in college I lived in the basement of a big, old house operating as a small inn. I always parked my car in the same spot on the curb on the east side of the house, where an overgrown stone walkway led to the back door. Winter nights, returning from an evening class or the Coffee House or my boyfriend’s dorm, I’d look up and try to find Orion’s Belt. I don’t remember how it started, only that those three stars became for me an anchor in the sky. On nights I was calm or lonely or desperately sad or purely happy, I’d look up in search of the three twinkling points and feel somehow placed, recalibrated.

Such were the oranges, small anchors pinning together disparate memories, marking spans of time. They are how I travel back there in my memory; I briefly reinhabit the mind of the person I was then, and remember what it was like when that place was home. It’s all real somehow because of that image—a piece of fruit on the ground.

Other notable finds from my five years in Boston include a green wig, three left shoes arranged in a neat row, a blue card with white type reading “What happens after I die?,” a large, completely full iced coffee (heartbreaking), a vase of flowers.

The other day I was reading The Rituals of Dinner by Margaret Visser, and was gifted this delightful phrase from a Victorian etiquette manual: “Never embark on an orange.”1 “Embark,” as if it were a perilous journey, eating an orange. Maybe it’s not fair to mock. Eating an orange within the rigid confines of Victorian-era table manners? Perilous indeed.

Emily Post in 1922 wrote,

Never suck an orange in a restaurant, or at a table anywhere – unless at a picnic. You can peel it and divide sections and eat it in your fingers; or cut it in half and eat with a spoon, or cut it in any way you like best. My own favourite way is to cut off the rind with a sharp knife, then holding the fork in the left hand and the knife in the right, cut the peeled orange in half crossways and cut into small pieces and eat with a fork.2

A manners guide in 2000:

At an elegant meal, a slice of orange is peeled with a knife from top to bottom in a spiral motion. The orange is cut in half lengthwise and the segments are eaten with a fork and knife. At a family meal, the orange peel is scored, and the fruit is peeled with fingers. The segments are eaten with fingers or a fork and knife.3

(The first sentence begs the question: who, at an elegant meal, is placing in front of their guest a whole, unpeeled orange?)

This 2021 TikTok insists on using cutlery: “slice it like a cake!”4

“Absolutely not,” says my dear friend K in response to the above video. “Eating an orange should appeal to our basal instincts to disembowel a small prey animal using only our teeth and hands.”5

Which is a nice segue into r/ShowerOrange, a subreddit comprised of individuals who are “dedicated to the consumption of various citrus fruits whilst taking a shower.”6 Scrolling through, it’s mostly photos of disembodied hands holding oranges against backdrops of neutral-colored tile, with a showerhead or shampoo bottle somewhere in frame. Many are posted by first timers excited to embark on their inaugural citrusy shower.

First impression: Huh. Okay.

Second impression: These people’s showers are way cleaner than mine.

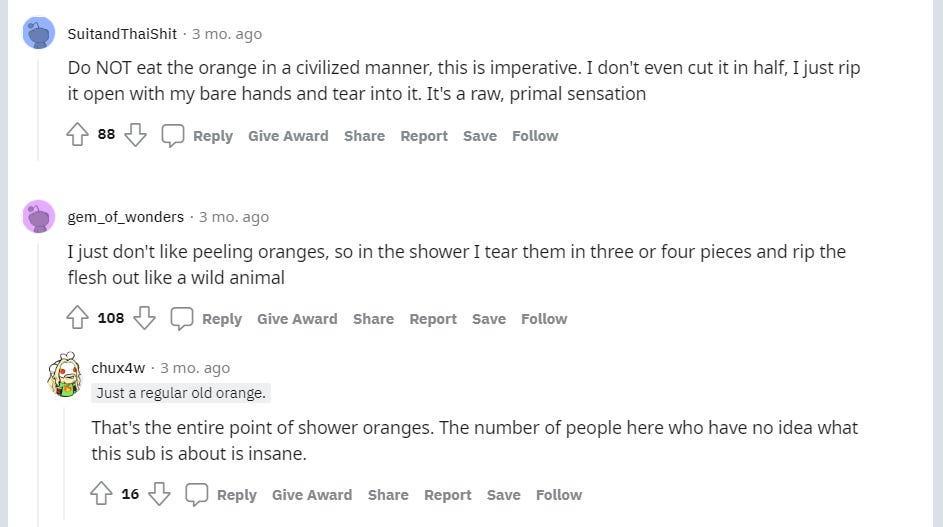

I click on a few posts, scroll through the comments. Die-hard shower orangers (orange showerers?) speak of the ritual with intriguing reverence bordering on…eroticism? “[T]he ability to eat the orange savagely and unabashed when the oil in its skin hits the steam and it’s [sic] cold juice runs down your chest…”7 I find a post titled “I want to understand.” Same. Give me a direct explanation. “I have tried it,” the post reads. “I ate the orange, I took the shower. I just do not get it. I want to know what it is that you guys are so thrilled about. Am I doing it wrong? I just take a hot shower and then eat the orange? Is there anything else to it?”8 Several comments query whether the orange was cold—the orange must be cold, I’ve learned. Other Redditors suggest mangos. One user acknowledges that it could just come down to preference: “you’re either into or ya ain’t.”9 I found the following to be the most clarifying exchange:10 11 12

Every etiquette guide I’ve encountered has presupposed that the best place to eat an orange is at a table, a picnic, basically any setting governed by “the constraints and the ornamentations which characterize polite behaviour.”13 And so their question becomes How best to eat an orange? Hence the instructions on manipulating the rind using a fork and knife, advice on when fingers are acceptable, etc. The shower orangers, on the other hand, presuppose that the best way to eat an orange is brazenly, crudely, tossing aside any concern for cleanliness or precision or the slightest of social mores. Their question, then, is Where best to eat an orange? Except they’ve answered it: in the shower. A place where manners are moot, mess irrelevant, and polite company…well, impossible. Where we can stop pretending we aren’t animals and go ham on a piece of fruit. “Carnal, ferocious, liberating.”14 I get it. Shower orange.

3.

J and I moved to Boston after a year and a half of dating. We had both recently graduated college, and he was working as a research assistant at our alma mater, I at a bookstore. Neither of us had lived anywhere but our hometown, and the possibility of going somewhere new soon eked into our heads; when J applied to a handful of graduate schools both near and far, we assumed the choice would be made for us. Not quite. Two schools accepted J: one in our hometown, the other 1,500 miles away in Boston, Massachusetts. For months we pondered, both together and separately, the prospect of leaving. I can’t speak for him, but I think I knew right away, in some deep, still part myself—it’s time to go. But to leave the only place in the world we’d ever really known was not a decision we were ready to make quickly or cleanly. Bit by bit we let our minds widen to the possibility, the exhilaration, the full, dazzling life of it, and of course, of course! We went.

In Boston, J began graduate school and I, through a classmate of his, settled into a serving job at an old private club founded by a group of Boston Brahmins who sought to mimic similar clubs in England. (“You cannot keep a room full of Anglo-Saxons waiting for cake this long, they start to form more clubs.”15) My first day was their annual Christmas party, largest of the year, with some two-hundred guests. Every room was filled with tables that, over the course of the afternoon, we would laden with elaborate settings—rows of silver flatware, glasses for white, red, dessert wine, champagne, butter plates, cruets of olive oil. Napkins pinwheeled and notched into glasses. Sumptuous floral arrangements and fresh-cut tapers. Finger bowls and crumbers at the ready on credenzas. During cocktail hour, as the guests flooded the bar and halls and sitting rooms, one of the managers, a kind, funny, elegant woman who I would come to know and admire, gathered the new servers in the main dining room and guided us through steps of service. Which, it turned out, were many.

Forks are placed to the left of the set plate, knives and spoons to the right. The outermost flatware is used for the first course, and the guest works their way in as the courses are served. There are three exceptions: the oyster fork, the butter knife, and dessert flatware. The oyster fork is not preplaced but is added right before the course, with the points balanced on the blade of the outermost knife, the handle angled down and to the right. The butter knife is placed directly on the butter plate, which, depending on the setting, is placed above or to the left of the set plate. Dessert flatware is placed above the set plate, parallel to the edge of the table. The spoon is above the fork, with its handle pointing to the guest’s right. The fork is below, its handle pointing left.

The water glass is placed above the innermost knife. The white wine glass is placed behind and to the right of the water glass, and the red wine glass is placed behind and to the left of the water glass.

Plates and bowls should be served from the left with the left hand, and cleared from the right with the right hand. The same goes for placing and removing flatware. The goal is that the server’s reach never crosses the space in front of the guest, and the server is always politely angled towards the guest as they serve and clear.

The host should be served and cleared last. The guests are served counter-clockwise around the table, beginning with the guest to the host’s right. Dinnerware is cleared clockwise around the table, beginning with the guest to the host’s left. This is done so that the server is essentially moving forward around the table: serving with their left hand counter-clockwise, and clearing with their right hand clockwise.

All guests must be finished eating before the course is cleared. The guest will use their fork and knife to indicate whether they have finished. If the guest has merely paused, they will place their flatware on the plate in an upside-down V, with the head of the fork and knife forming a point at the top of the plate. When the guest is finished and ready for their plate to be cleared, they will place the fork and knife, parallel to each other, diagonally across the plate, with the handles angled down to the right. After each course, all corresponding flatware should be cleared regardless of whether it has been used.

After the penultimate course has been cleared, and before the dessert course is brought out, the table space in front of each guest should be crumbed. This will require some crossing in front of the guest, but it should be done as unobtrusively as possible, and without moving any glasses. Once the table has been crumbed, a fingerbowl is placed in front of each guest. While the guests are using the fingerbowls, the dessert flatware should be brought down from above the setting: the spoon is brought down and placed to the right of the setting, the fork to the left. When the dessert course is served, the fingerbowl should be moved to the upper left of each setting.

M, the bartender, showed us how to present and pour wine—how to display the bottle on the serviette, remove the cork silently, decant by candlelight, pour without dripping. After a time, he said, we’d be able to pour equal servings based on pitch alone, as the liquid extends into and rises up the belly of the glass.

After a few months, all these rules had stopped jumbling around my head and settled into my movements, and I could more closely observe the behaviors, both the guests’ and my own, and the effect they had on a meal. I liked the way it felt, all these precise movements, choreographed like a dance; each night all of us slipping into a quiet performance. There was a beauty to it. Not to this system of etiquette necessarily, but etiquette in general, as a form. Why? Where did this beauty come from? In part it came from the utilitarian nature of some of the rules (this seemed paradoxical at first; too often the whole affair was dressed up to the point of pretention). For example, the way the guest places their fork and knife to indicate that they have finished. This meant I could confidently transition the group from course to course without interrupting the meal, and without anyone feeling rushed. I saw how such rules contribute to the elegance and beauty of a meal in that they preserve the flow, and intricate intertwining, of the gastronomical and social experiences. If each knows and sticks to their behaviors, the server and the guests run parallel to one another, easing the evening along, never colliding.

Form itself lends beauty. Dining etiquette as a form takes a biologically necessary act—supplying our bodies with sustenance—and exalts it, giving it weight and allowing it to transcend into the realm of aesthetics. Like how music as a form, for example, can mold ideas, emotions, impressions, experiences into a piece of art all its own.

Finely rendered form reflects care and intention, and these I believe are their own kind of beauty. Such qualities are often indicative of love, respect, general high regard—for what is being made, for the emotion conveyed, for those who will experience it. This extends beyond art. Think of the most basic, most human act of caring: lending time and attention to another person. I think of my grandmother, who for several years cared for my grandfather in his illness. It was not beautiful, romantic work. It was raw, grievous—bathing, dressing and undressing, helping in the bathroom, holding one’s own in the face of jargon-spewing doctors, enduring verbal gymnastics with insurance representatives. The loneliness and the guilt, perhaps, of being the only healthy, able one. And the grief, the pain, not only in witnessing the deterioration of this vibrant person but, I imagine, in the knowledge that this is how it ends: this is how we spend the last of our time together. I have witnessed few things rendered so beautiful by dignity and intention than the act of my grandmother’s care during those years. It warrants the reverence of the world’s greatest art.

Beyond beauty, there is the good old comfort of ritual, of knowing what step follows what. Outside of work, my life felt like an explosion in slow motion. I didn’t have the self-discipline to do any real writing, and I didn’t have the drive or focus to build that self-discipline. My relationship with J, our future together, seemed to be getting further and further away. I was falling in love with someone else who made me feel like a real person. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, didn’t have a plan; “no plan” wasn’t even my plan—there is dignity in that at least. I couldn’t wrap my head around life, and yet, like everyone else, I had to get up every day and live it. And so I leaned into the warm hypnosis of dinner service, the precision of which acted as a balm upon the chaos of my life. I didn’t have any answers—didn’t even know the questions—but I knew what each evening would look like, I knew how I was supposed to behave, and the guests knew how they were supposed to behave, and there was a comfort in that. We knew our roles. They were good roles.

I almost forgot—the beauty of form as a rejection of form.

It’s one of those blinding, shimmering winter mornings, when the sunlight is as bright and sharp as the cold. I pool into my big green puffer coat and lumber the two blocks to Busy Bee Restaurant, a family-owned (since 1967), no-nonsense diner obstinately located between a yoga studio and a Whole Foods. I enter, the bell on the door clinks, I take a seat at the counter, and in a moment that is seared affectionately into my brain forever, I am tossed—tossed—a knife and fork, which clatter on the counter and land askew, nowhere near the napkin that at the same time was slid not so much towards me as away from the hand doing the sliding.

You know when you’ve had a long day, and you finally get home and can take off your shoes? You’re a fan of the concept of shoes. You’re a fan of the reality of shoes, these ones in particular: they’re comfortable, they’re you, you put them on and feel like a million bucks. But still, the moment you slip them off and stretch your feet in the open air—b l i s s.

I collect the fork and knife, straighten them on the napkin, sit hunched over the counter, chin in my hands. Formlessness defined still by the form it seeks to shed. There is so much that is beautiful.

4.

Sometimes I think the true mind is in the belly, in the pump of blood and breath, the churning of flesh through flesh. We call it gut, we call it instinct. There is, somewhere buried, a knowing—who to hang on to, who to let go of; the time for beginnings and endings; when action moves and grows things, and when respite does.

Who can ever say how it happens? I suppose in some cases it’s clear, there’s a rift or a revealing of true character and the love drains away like blood from the face. Certainly, J and I had our problems, but for me at least, there was never a real break, no moment of fracture. It was like—well, it was like the snow I’m watching now as I eat this orange on the patio: pocking and shrinking apart from itself and yielding to the ground that was always beneath. Gone in the slow swell of warm air.

What if love from past lives is buried deep inside of us, in the material of our bodies? Or dispersed, pieces of pulverized shell winking amongst sand, sand, sand? And we can love now because of all these past loves, dim within us until they sense a familiar and begin to glow and beam towards it like live blood towards live blood?

Who can ever say how it happens? I certainly can’t. I only know that for a year, he was just M, the bartender, my friend—sociable, kind, intelligent, always late—and then something began to shift, a knowing began to rise like ice dislodged from the bottom of a glass. I do remember when this knowing quietly broke the surface (and suddenly there is air, horizon), when, you could say, I knew I loved him, though it was a “love”-less love, wordless, wholly beyond articulation.

It was a Thursday in November. It was before dinner service, and all of us—servers, bartenders, maître d—were gathered in the back pantry, waiting for the first table to arrive. M was talking—a frequent state—and I don’t remember what he was saying, it didn’t matter what he was saying. I was looking at him and in my chest was a wide, warm, crucial, reaching ache, as if he were someone I had loved long ago and was now meeting again. It didn’t feel just mine, this love, but ancient, passed down from those who are as much strangers as they are my very marrow. Some heirloom cold and glittering in mine, the latest palm.

Maybe I’m trying to say this: he felt like home.

J knew I was in love with M. Late one night, I’d drunkenly spilled all my confused, conflicting feelings into my notebook and torn the page out the next day with the intention of ripping it up and throwing the pieces into the trash can at Fenway Park station. Instead I became engrossed in whatever else I was writing, and the page got lost in the folds of the blanket, and J found it, and it was not good. I don’t remember what either of us said during that encounter. I only remember the excruciating panic when he told me he’d found it, the realization of what “it” was, that “no no no no no no” sort of rejection in the mind, the need to bury my face in my pillow. I remember an agonizing Friendsgiving the following day, the creaky smile I put on. I remember being alone in the apartment for a few days and nights while J stayed with a friend. I remember not having the guts or certainty to end it there, let it be over and dead. I remember the sky that afternoon, the day I tore the page from the notebook. It was so wide, blatant, aching. I took a picture from the front door of our building, the green-trimmed eaves of the building across the street jutting into the vast, flat blue.

We’d hang on for nine more brutal months.

What if love is given to us by all the loves before, and all the loves before those, and all the loves before those? And we give it on?

“You’re staying in Boston? Don’t tell me you’re staying for M, I swear to god—”

“I’m not staying for M.”

“Then why, why wouldn’t you just go home?”

He sounds incredulous, angry even. How dare you stay here, he seems to say.

“You know all of the time that you have had here? You know all of the people you’ve met, and the experiences you’ve had, you know how it went from being a strange, unfamiliar place to home? You know how you can recognize the city now when you fly in, you can see where you’ve lived, where you’ve had all these moments? I’ve had all those moments too, for myself. Every year, month, week, day, hour, minute, second you have lived here, and built a life here, and a self here, I have too. I am as real in this place as you are. My life is as real as yours.”

I didn’t say any of that.

5.

Always embark on an orange. Dive into the mess, the effort, the clamor of it. Curl your fingers like claws. Dig nails into the pith. Accept—no, relish—the juice slicking your wrists and chin, like when you were a child and food was food and hands were tools and you trusted your tongue and a book about eating would have seemed absurd, you do it so well already! Pull apart the carpals and listen for the muffled rip as they cleave. The vesicles gleam, compact as muscle. Eat one slice, give one away, love me love me not, to a friend, a stranger, the dirt that made you. So many hands in your hands, echoes dissecting, hold those hands up to the sun. Fingertips tender from the press of digging and tearing, cuts smarting and newly alive. Just like the moment.

—AKB

Anon, quoted by Margaret Visser in The Rituals of Dinner (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), 287. (Despite the references in Visser’s book, I cannot for the life of me determine the original source. It’s likely one of the sources listed under “Anon” in Visser’s bibliography.)

Emily Post, Etiquette: The Blue Book of Social Usage (New York and London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922), 761.

Suzanne von Drachenfels, The Art of the Table: A Complete Guide to Table Setting, Table Manners, and Tableware (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 520.

Sara Jane Ho (@sarajaneho), The Proper Way to Eat an Orange #etiquette #etiquettetips #tablemanners #lifehacks #food #tips #fruit #orange #lifestyle #cutegirl, TikTok, August 9, 2021, https://ww.tiktok.com/@sarajaneho/video/6994611723328146694

Kate W., email message to author, January 19, 2023.

"Shower Orange an Enlightenment of the Soul (r/ShowerOrange)," Reddit, accessed January 15, 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/

shrimpsh, "Was the orange cold?" September 30, 2022, comment on shoks1995, "I want to understand," https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/comments/xrvua5/comment/iqhizwk/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

shokz1995, "I want to understand," Reddit (r/ShowerOrange), September 30, 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/comments/xrvua5/i_want_to_understand/

shrimpsh, "Was the orange cold?" 2022.

SuitandThaiShit, "Do NOT eat the orange in a civilized manner," September 30, 2022, comment on shoks1995, "I want to understand," https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/comments/xrvua5/comment/iqikhrl/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

gem_of_wonders, "I just don't like peeling oranges," September 30, 2022, comment on shoks1995, "I want to understand," https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/comments/xrvua5/comment/iqhau9s/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

chux4w, "That's the entire point of shower oranges," September 30, 2022, comment on gem_of_wonders, "I just don't like peeling oranges," https://www.reddit.com/r/ShowerOrange/comments/xrvua5/comment/iqk99mx/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

Margaret Visser, The Rituals of Dinner (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), 167.

"Ok so this is going to sound real weird," April 14, 2015, comment on "What's something unconventional everyone should try out?" Reddit (r/AskReddit), https://np.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/32jwie/whats_something_unconventional_everyone_should/cqbwlwi/

Amy Sherman-Palladino, dir. Gilmore Girls. Season 5, episode 13, "Wedding Bell Blues." Aired February 8, 2005, on The WB. https://www.netflix.com/browse?jbv=70155618

Your description of the Christmas party at the club brought to mind an elegant meal I had in the spring of 1966 in Stillwater, Minnesota at the Lowell Inn, as guest of a business associate and his wife.

The dining area was a large, quietly lit room with maybe fifteen round tables dressed in large white cloths, all occupied, and tended by young girls in white gowns who seemed to float like ballerinas among the guests. The place settings were elegant, but understated, and there was a fresh bouquet. Once seated, the service seemed omnipresent, effortless, and smooth. I’m sure the meal was exquisite, the conversation may have been profound… but I remember mostly the girls and the sense of dining in a Viennese ballroom. I’ve never experienced anything like it since.

At its meanest level, food is fuel, but it can be elevated to high art. And high art or no, any meal, carefully, competently, lovingly prepared and served is due great attention and respect.

What a talent you are! I feel myself walking in your shoes, seeing and feeling what you do. Thank you for the beautiful trip you let me join you on.